Firing the Bad Cop

Image courtesy of cyril chermin via flickrI pay a bill each month--actually, multiple bills--that give my family access to all kinds of information and the ability to communicate with people around the world. It's a beautiful thing, really. If I want to know what temperature it will be when we arrive at the beach, it's there. If I want to know the name of the guy who invented the whoopee cushion, I can have the answer in seconds--kind of. If I want to know how old Judy Garland was when she played Dorothy, a few keystrokes, and I have my answer. It's almost like magic.

I also have five kids. Great kids. Funny kids. Talented and smart. The combination of the magical worldwide window we call the web and the curious creatures that are children has resulted in a number of interesting and sometimes uncomfortable conversations in our home. As a parent, I feel it's my job to protect my children from unpleasant and potentially damaging media they might encounter when they are young. As a woman, I'm angry that so much of what is broadcast on the Internet is unrealistic and disrespectful toward my gender. My goal, too, as the mother of boys, has been to teach them to see women differently, to treat women differently, to be human beings that reject objectification and embrace intelligence, respect, and the value of a person as a person, complete with thoughts and feelings and a history and a future.

There's so much stacked against us, though, both guys and gals. Images and stigmas and expectations.

When my older kids were younger, and I discovered someone looking at porn or reading elicit stuff online, I had two strong and immediate reactions--anger and betrayal. I felt their decisions to ogle naked bodies on a computer screen were a direct insult to me personally. I feared I had failed my children. I feared I had failed my female sisters. I feared I had failed in upholding my ideals in general as a parent and as a woman. Anger, as I have since learned, is a smokescreen for fear, so my first reaction to the person who I had perceived as betraying my trust was, of course, anger.

I'm sorry now that I expressed such anger and foisted shame on the people I love. I can only plead ignorance in knowing how to handle my feelings of betrayal and embarrassment. I guess I could even say I acted out of laziness. I didn't want to try to communicate because I didn't want to face the embarrassment or put my thoughts into constructive words. It's easier to raise voices and place blame.

By now, I've learned a few things. It certainly took some trial and a lot of error. One of the things I've learned is that calm communication, in any form, is better than anger. Recently, when I suspected one of my younger children of seeking unhealthy images on the Internet, I pushed away the feelings of betrayal and fear and called instead upon reason and empathy. I know what it's like to be curious, and I know what it's like to be shamed. One is a natural part of growing up. The other is a form of control bourne out of laziness and fear. I didn't want this person I love to feel ashamed or distanced from me. I wanted them to be informed, to know they're normal, to understand that there are healthy ways of approaching curiosity and potentially damaging ways of attempting to satisfy what our brains and bodies get all fired up about.

So I sat down with this person I love, and I said, "Here's the thing. What you're feeling and wondering about is completely normal. There's nothing wrong with wanting to know what bodies look like, what they do, how they fit together, and how that might feel. Everyone wants to know those things. Every. Single. Person. And if they tell you they don't, they're probably lying."

I went on to tell this person I love about the time when, around their age, I stumbled upon a stash of porn belonging to an adult I loved and trusted. There were images there that haunt me to this day, not only because they were completely out of context, and I was unprepared for them, but because they were demeaning to women and to human beings in general. Recalling those images now also recalls the painful memories of how that same adult I loved and trusted one day found a stash of nude drawings I had made and approached me enraged, screaming about how bad I was for drawing them, making me throw them into a steel barrel and set a match to them. I was horrified and, yes, ashamed. I feared that there was something weird about me for being curious and having sexual feelings. For the rest of my adolescence, sex was taboo, a topic I knew would make the people who loved me very angry, possibly even causing them to reject me.

After I shared that story with this child I love, we talked about being curious, about asking questions to the people you love and trust and not seeking answers through questionable sources like random searches on the internet. I also did something I've heard you should never do--I handed over a book full of information from a source I trusted, a source that offered all kinds of answers, written for this child's reading level. The next day, I asked how it was going, and the child said they had read the ENTIRE book. And liked it! We had a good talk, and now, whether through face-to-face questions, emails, Facebook messages, or texts (no form of communication is invalid), we can talk about the questions. No anger. No fear. No shame.

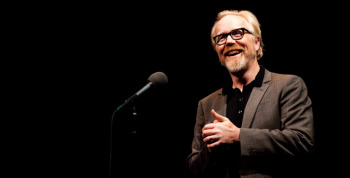

Last week, I listened to a podcast I love called The Moth, which is committed to recording true stories, told live on stages across the country, without notes. It features a variety of people from all walks of life, both everyday folks and celebrities. The podcast I listened to included a story by Adam Savage, cohost of one of my family's favorite shows, Mythbusters. Savage approached the subject of raising kids in the age of the Internet with thought, honesty, and humor. In his talk, he shared how he initially went the route of the "bad cop," but then realized it was better to simply discuss the issues.

I'm including the transcript of the talk below, for those who prefer reading over listening, but listen if you can (it's segment one), because his delivery is great.

Bringing things like Internet porn out into the open with honesty, fact, and humor does a fabulous job of crushing shame and insecurity, not just in those we love, but in ourselves, too. It takes away the power of that shame and replaces it with the knowledge that we can talk openly to those we love, those who will support us and love us unconditionally. When we fire the bad cop, we foster great conversations that make positive, lasting impressions.

The Moth: Talking to My Kids About Sex in the Internet Age by Adam Savage

'I have twin boys, Thing One and Thing Two. I have worried, I have worried since before they were born about how to properly prepare them for the world, how to give them the best information to be good humans and have good lives. I think of their brains like computer programs, like computers, and they're running all this custom code. It's not all my code, unfortunately. Only about 10% of the code they're running is mine. The problem is, I don't know which 10%. I have no control over what they prioritize. See, at first, it's really easy, and it's like training dogs, right? With babies, you just accept the behavior you're willing to live with, reject the behavior you're not willing to live with, and there's a lot of fluid cleanup.

But something happened to my kids the moment they started to leave the house for daycare, for kindergarten, for first grade. Two things happened, actually. The first thing is they started getting information from sources other than me. They started running outside code. The second is they started behaving like people that I'd never met before. And I would get this call from school. Is there anything worse as a parent than a call from the school? 'Ah, hello, Adam. This is the school calling. Uh, we just want to let you know that at 2 o'clock today, out in the yard, you failed as a parent.' I'm pretty sure that's what they said.

So, you get them home at the end of the day, you figure, all right. Time for some parenting. You sit them down. What do you talk about? Well, if they stole something, you talk about honesty. If they lied about something you talk about honesty. That's a regular refrain. If they hit someone, you talk about anger management issues, and you use other words, like, 'Use your words.' It's all like you're trying to run code to get them to not do the same behavior the next time.

And how are you doing running that code? From the looks on their faces, I wasn't doing very well. My kids, very early on, perfected this blank stare, this, 'I'm not gonna give you anything to get upset about within these parameters, and I'm just gonna wait for you to be done.' This is not an environment that's conducive to running deep code.

And the stakes are high. I remember being five years old. I remember being in kindergarten and I got pushed off the swing by a classmate named George who was black, and he stood over me while I was out of breath, not even having a breath to cry with because I was in so much pain, and he laughed at me. And I went home, and I asked my mom…I was really unhinged by the fact that he was laughing. Not the injury, but his delight in my injury. My mom sat me down and she said, 'Well, black people have a lot to be angry about with white people. There's long history that's difficult…,' which she explained: slavery and racial matters and everything. I understand what she was doing. She was trying to give me some context. My five-year-old brain doesn't know context. What she said was, 'The situation is bigger than you currently understand.' What I heard was, 'You're part of the problem.' And for the rest of my life, even today, I meet a black person, and some part of my brain goes, 'I hope they realize I'm one of the nice ones.'

So the stakes are high. But what can you do? You get the call from school, you bring the kid home, you talk to him. Somewhere in the fourth grade, we hit the real talk. Apparently, according to the daycare teacher, my son, Thing Two, had gathered his friends around him, and said, 'Come here. I've got something to tell you.' Clearly inspired by one of the inappropriate movies I had taken him to. He explained that, 'when you get older, you get a girlfriend, and you have sex with her.' Like it's a bar mitzvah gift.

So I get this call, and I figure, alright. Time for the sex talk. Feels a little early, but alright. I sit them down on the couch in front of me, and I say, 'So, you know, guys, this happened, and I just want to know, what do you know about sex? Do you know what sex really is,' and they're like, 'Yeah, we totally know, Dad. We totally know. We have no idea. None.' I'm like, okay, good. No reason not to be technical, so I go into some fairly great details about their private parts, what they are, how they work, what they do, where they go, and I'm embarrassed,too.

Two things are happening with them. One of them is that they each grab a pillow and hold it in front of them like a giant shield. It's hilarious. Clutching it. This look on their face. I look up, and I see the look on their face, and that look is one of undivided attention. It's full of terror and embarrassment, too, but attention.

And in that second, I become a complete fan of talking to my kids about sex. When else am I going to run code this pure, this deep, on a level that's really getting to them? So we have a bunch more sex talks over the next few years. And they go fine! I say some funny things, I say some real things, I think I'm really getting to them, but the whole time, all I'm really thinking about is how to approach this aspect of their lives that I didn't have to deal with when I was a kid. The Internet. We didn't have 24/7 delivery of porn to every device strapped to our bodies. Don't get me wrong. I wanted that. But I had to find my porn by the side of the highway, and I was grateful.

So I'm about to tell you about the experience of catching my kids surfing porn, and I'm gonna tell you one kid's story, but the thing you should know--both kids' stories are nearly identical, except for a couple of details. In both cases, I got an email late on Sunday night from their mom, who I'm divorced from--we share custody--sending me a linkdom, probably just before her computer was totally crippled by malware, of their search terms. As a side note, I have my children's first porn search terms. It's like almost better than their first steps. Thing Two's first search term? Nudies. Not what he was looking for. Turns out to be some sort of areola-hiding garment for sheer dresses.

The other thing, Thing Two was the first one to be caught, and the other difference between the two of them is I attempted to play 'bad cop' with Thing Two, and I was met with a complete stonewall. And then I thought about it, and I realized, I'm not really that angry about what happened. I'm mean, actually pretty sanguine about it, and we could talk about it.

So when it came around to Thing One, I didn't go through 'bad cop.' He merely got in the back of my car, and as we drove to breakfast early Sunday morning, I said, 'Listen. What you did is totally reasonable. Being curious about what people look like naked is a rational and normal response to the world, and it is a reasonable curiosity for you to have. No one's in trouble, and I'm not mad. Now, is there something you want to tell me.' And there's this pause in the back seat, that pause you know as a parent means, 'Ahhh. I've got them.' And he says, 'I searched for big boobs!' Somewhere in my head is an interrogation room and a two-way mirror behind which two detectives are high fiving that I've just nailed the perp. And I start to talk to him about what he saw, and how he felt about what he saw.

But, again, all I'm thinking about, really, is the 800-lb gorilla in the room. Not what he saw, but what he's gonna see.

So I tell him, 'You gotta be careful out there. It's reasonable to be curious, but your curiosity is gonna pay off really, really unpleasant dividends pretty quickly.'

He's like, 'What do you mean?'

'Well, there's some really awful stuff out there. Genuinely, genuinely awful stuff.'

And I see it in his eyes. Actual curiosity. That's bad. I don't want that.

So I tell him, 'You're going to see things you will never be able to unsee. Things that will stick in your brain and ruin moments for you because they'll show up and screw over your brain because it won't be able to think about anything else but that horrible thing you saw once when you were 12.'

And now I see fear in his eyes, and I realize he's 10 or 11, and I'm still reasonably omnipotent. I've maybe scared him away from the Internet for a year, but not much longer than that. So how am I gonna prepare him for what he eventually sees? I thought about myself at his age. I thought about my classmates, Caesar Ortega, bringing a skin mag to middle school, and showing us pictures that I found upsetting, and I thought, what would I have wanted to hear at that moment? What would have helped me with that?

And then I thought about my mom trying to give my five-year-old brain some context about racism in the United States. This conversation between my mom and I occurred only seven years after the Civil Rights Act had passed. This stuff was fresh and is fresh to our generation, and I think about that in direct contrast to the blissful lack of racism in my own children, who have been lucky enough to grow up in such a diverse, liberal city as San Francisco. And then I think, this is where cultural change really occurs, generationally. And if the stakes are this high, I better get this right. I better be concise and succinct.

And then it hits me what I'm supposed to say, and I say:

'The thing you've gotta understand, Bud, is the Internet hates women.'

And I recognize there's probably those out there who are thinking that's an incredibly broad brush to pain the Internet with, but let me put it this way. If you could look into someone's brain the way you search the Internet, and the Internet was a dude? That dude has a problem with women.

I realize this is the code that I wanna run, and he's old enough to run it. I want him to realize that, even by the chance dint of his gender, if he's not part of the solution, he might very well be part of the problem, and I want him thinking, when he talks to women, 'I'm one of the good ones.'